An Interview with Meg Eden

by Laura Shovan

I have a vivid memory of the first time I met poet Meg Eden in person. I had published a poem of hers, “Letter of the Day (Autism Pantoum),” in the literary journal I was editing at the time. We had coffee and pastries at a local Korean bakery. At the time, Meg was in grad school and wondering whether it was possible to be both a poet publishing in literary magazines and a children’s book author. Answer: It is.

Many years later, I was lucky enough to read an early draft of Meg’s debut middle grade novel, written in verse. Good Different (Scholastic, April 2023) is one of the best autism representation stories I have read. Which is no surprise! Meg is a fine, observant poet who also identifies as autistic.

Meg and I had a conversation about novels in verse, hair-touching, and what she hopes readers will take away from Selah’s story.

Aside from the fact that you are an accomplished poet, Meg, what made verse the best fit for Selah’s voice?

It wasn’t something I decided; Selah just came to me in poems. I can’t just sit down and decide I’m going to write a verse novel (when I’ve tried, it hasn’t worked out very well…). The content has to demand verse—it has to carry such strong emotion that prose just doesn’t feel like enough.

Like Selah, many girls with autism are misdiagnosed or diagnosed later than their male peers. Why was it important to you to reflect this in Selah’s story?

Being misdiagnosed or not diagnosed at all can feel awful. The experience really varies for everyone, so I don’t want to generalize, but for me, I always felt different—and often that was celebrated and very good, but other times I felt like I was missing out on a joke everyone else was in on. And as I hit adulthood, I felt like I couldn’t keep up. Because I didn’t have some diagnosed ailment, I wondered: am I just lazy? Do I have a bad attitude? Why can’t I keep up? I didn’t realize I had literal, neurological differences. I know for me, having a name was so empowering, and is gradually giving me the courage to ask for help. So my hope in sharing this story is that it can help validate kids who feel different, that they CAN fly—they just might need tools to help them. And if they are undiagnosed, like I was, maybe this can be a first step for finding a name for what’s going on. Like you said, girls are much more likely to be misdiagnosed or to fly under the radar for so many reasons. I hope this story can help them feel seen, that the way they are isn’t “wrong” and that they are so strong, like Selah. I hope that particularly neurodivergent girls reading can see autism as a possibility for them—because for so long, it wasn’t even something I knew was possible for me. But also, I really want adults and neurotypicals to read this and see that there may be some kids they make assumptions about—who really are autistic and need allyship, not judgment.

Let’s talk about hair! Touching someone else’s hair without permission can be triggering for many reasons, including body autonomy. For Selah, uninvited touch is a sensory issue and an invasion of her space. But braiding hair can also be a form of bonding, a sign of friendship. How did you navigate this complex topic in your novel?

I love that you bring this up! The way I navigated it was how I navigate many things: starting with my feelings/personal response, then exploring what the other person might’ve been thinking, or why they did this thing that surprised me. By having to think about the other person’s perspective, I build empathy. I also come to realize that there can be lots of things going on at once, and practice holding those multitudes in my hands. My perspective’s not the only perspective in a given situation.

As I dissected this memory of this girl braiding my hair without my consent in school, I was initially only in my feelings: that it was strange and confusing that she didn’t ask first, how I felt like I couldn’t say anything, and how it hurt--and all of this is, of course, valid. But then I began to think about the other girl’s perspective, and I realized that she was probably doing it as a way to try to reach out and connect to me. That she liked that sort of thing, and she was trying to build a relationship by giving what she saw as a gift. This girl was so kind and sweet, and always reaching out to be a friend to me, so I know it came from a well-meaning place. Reflecting on this made me want to portray the character Addie’s complexity in the novel: that she means well, she’s just very different from Selah, and that in the future she should always ask before touching someone’s hair.

I hope that readers can go through a similar process, acknowledging the importance of body autonomy and consent, but also seeing that people reach out and show love in different ways, and navigating a way to acknowledge both of these realities simultaneously with empathy and kindness.

Let’s talk about conventions! Selah is passionate about dragons, something she’s sure her classmates won’t understand or accept. When she goes to her first fan convention, Selah is both overwhelmed and delighted to meet people who are celebrating their favorite fictional characters, fandoms, and mythological creatures. How are cons “good different”?

I love cons, because I think for so many of us neurodivergent folks, we’ve felt so isolated in school or home because of our differences—but then we go to this magical place with all these people like us! We realize we’re not alone, in our neurodivergence, but also in our special interests. Cons are basically gatherings for the “good different.” They are a space where the different is celebrated, and where I’ve definitely felt affirmed as “good different.”

How would you like to see classrooms engaging with Good Different and Selah’s story?

I think there are so many cool ways to engage with Selah’s story in the classroom, and educators—if you want to talk more about this topic, ALWAYS feel free to reach out on social media or on my website. I think the way I’d love to see most is to have students respond through writing, reflection and critical thinking. Here is one idea:

Good Different came about from me writing a poem based in memory, that as I wrote morphed into something totally new! As I wrote about the memory of a girl braiding my hair in school without my consent, the speaker changed from me into this new character—Selah—when she did something very different than what happened in real life (I didn’t hit the girl who braided my hair!). Invite students to think of a memory that stands out to them, and rewriting the outcome of that memory. Start in the sensory details of the memory, but play with what happens next. What might you have felt or wanted to do but didn’t? What might’ve happened if you did that?

What are your favorite middle grade books with authentic autism representation? And what about poetry? Which poets for kids—and for adults—do you recommend?

I love Elle McNicoll’s A KIND OF SPARK and LIKE A CHARM for authentic autism rep, absolutely—and Sarah Kapit’s GET A GRIP, VIVY COHEN. Also enjoyed Meera Trehan’s THE VIEW FROM THE VERY BEST HOUSE IN TOWN.

As a kid, Naomi Shihab Nye was a gateway for me into poetry—I read 19 VARIETIES OF GAZELLE in high school and loved it!

Read Meg and Laura’s 2021 co-interview at Tinderbox Poetry Journal.

Laura Shovan

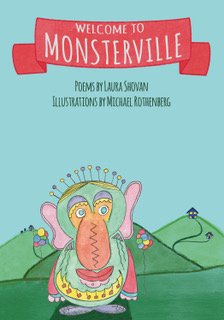

Laura Shovan is a novelist, educator, and Pushcart Prize-nominated poet. Her award-winning middle grade novels include The Last Fifth Grade of Emerson Elementary, Takedown, and the Sydney Taylor Notable A Place at the Table, written with Saadia Faruqi. Laura is a longtime poet-in-the-schools for her state arts council. She teaches for Vermont College of Fine Arts’ MFA program in Writing for Children and Young Adults. Her latest poetry collection for kids is Welcome to Monsterville (Apprentice House, 2023).

Meg Eden Kuyatt is a 2020 Pitch Wars mentee, and teaches creative writing at colleges and writing centers. She is the author of the 2021 Towson Prize for Literature winning poetry collection “Drowning in the Floating World” (Press 53, 2020) and children’s novels, most recently “Good Different,” a JLG Gold Standard selection (Scholastic, 2023). Find her online at https://linktr.ee/medenauthor.