GIVING VOICE TO THE VOICELESS:

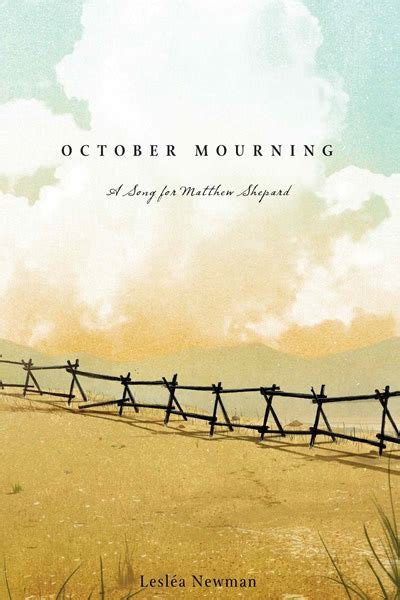

Persona Poems in October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard

When I was in fourth grade, I had a pair of red fake fur earmuffs, which I absolutely loved. How did the mean boys at the bus stop know how much I adored them? One cold morning as we stood out there, one of the older boys snatched my earmuffs off my head and threw them to another boy. A game of monkey-in-the-middle ensued, with me as the miserable monkey.

Finally the bus came, and I truly thought my torment would end. But instead, the meanest boy of all—the one who had originally grabbed my earmuffs—threw them down the sewer.

I stood there stunned. I couldn’t get on the bus and leave my earmuffs all alone underground, where it was dark, wet, and cold. The bitter tears I shed that day weren’t for me. They were for my earmuffs. I could only imagine their loneliness, their sense of betrayal, their utter despair.

I didn’t know the word for empathy when I was eight years old. I only knew what I felt. I had taken on the perceived emotions of an inanimate object that had been the victim of cruelty. To me, those red fake fur earmuffs were real. They meant something to me. They mattered. And they should not be forgotten. They held some truths. They held my truth. They embodied my loneliness, my helplessness, my sorrow. That day, and many days after, I felt worthless as a pair of earmuffs, lying in a pool of dirty sewage water.

Though I never wrote a poem about those earmuffs, I never forgot them, and this incident happened a good fifty years ago. But I have written many other persona poems as a way to express my feelings. In a persona poem, the poet gives voice to someone other than herself: another person, an animal, an inanimate object. Somehow this approach, which allows the poet to take a step back and observe with a keen eye, allows me to explore deep emotional truths.

I found this form of poetry particularly useful when writing my novel-in-verse, October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard. In 1998, Matthew Shepard was an out gay college student attending the University of Wyoming. On a Tuesday night in October, he was kidnapped, robbed, beaten, tied to a fence and abandoned. He was found 18 hours later by a mountain biker and rushed to the hospital. He died 6 days later with his family by his side, the morning of the first day of the University of Wyoming’s Gay Awareness Week, the morning I arrived on campus to be the keynote speaker.

How to write about such a brutal, heartless, unnecessary tragedy about which we will never know the truth? Matthew Shepard and his two killers were at the fence where his murder took place for approximately fifteen minutes. We will never know what truly happened there. Matt can’t tell us; his voice was stolen and silenced for all time. His killers, in my opinion, are not to be trusted to tell the truth; in fact their stories contradict one another. Since we will never know the factual truth, I decided to explore the emotional truth of the situation by giving voice to the animate and inanimate objects surrounding this event: the truck in which Matt was kidnapped, the pistol with which he was beaten, the shoes that were stolen from him, the moon that witnessed what happened to him, a deer that kept him company, and the fence to which he was tied.

I was particularly drawn to the fence, which immediately became an iconic symbol of the crime. To my mind, the fence was an innocent bystander, minding its own business, when all of a sudden, a truck pulled up, three men emerged, and a terrible act of violence ensued. One of the first poems I wrote for the collection takes place the night of Matt’s attack, and is written from the fence’s point of view. (It is also a pantoum). The poem, which is titled “The Fence (that night)” begins:

“I held him all night long.

He was heavy as a broken heart.

Tears fell from his unblinking eyes.

He was dead weight, yet he kept breathing.”

After I wrote this poem, I realized that the fence existed (had a life) before this terrible incident, and afterwards as well. And it had many things to say about the various roles it played. In addition to innocent bystander, the fence became in order: an unwilling accomplice, a witness, a caretaker, a crime scene, and a shrine.

In the poem, “The Fence (before)” which begins the collection, the fence is speaking about itself, but it also speaks for Matt Shepard:

“Out and alone

on the endless empty prairie

the moon bathes me

the stars bless me

the sun warms me

the wind soothes me

still still still

I wonder

will I always be out here

exposed and alone?

will I ever know why

I was put on this earth?

will somebody someday

stumble upon me?

will anyone remember me

after I’m gone?

The fence, which was taken down years after Matt was murdered, ends the collection, and again, speaks not only for itself, but for Matt as well in this poem titled, “The Fence (after)”:

prayed upon

frowned upon

revered

feared

adored

abhorred

despised

idolized

splintered

scarred

weathered

worn

broken down

broken up

ripped apart

ripped away

gone

but not forgotten

Giving voice to inanimate objects as well as to animals is an interesting way to look at a situation from a unique point of view and unearth emotional truths about the world in which we live. Try it!

“The Fence (that night),” “The Fence (before)” and “The Fence (after)” copyright ©2012 Lesléa Newman

from October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard (Candlewick Press).

Lesléa Newman

Lesléa Newman is a founding member of Diverse Verse and the author of 75 books for readers of all ages, including A Letter to Harvey Milk; October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard; I Carry My Mother; The Boy Who Cried Fabulous; Ketzel, the Cat Who Composed; and Heather Has Two Mommies.

She has received many literary awards, including creative writing fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Massachusetts Artists Foundation, two National Jewish Book Awards, two American Library Association Stonewall Honors, the Massachusetts Book Award, two Association of Jewish Libraries Sydney Taylor Awards as well as the Sydney Taylor Body-of-Work Award, the Highlights for Children Fiction Writing Award, a Money for Women/Barbara Deming Memorial Fiction Writing grant, the James Baldwin Award for Cultural Achievement, the Cat Writers’ Association Muse Medallion, and the Dog Writers’ Association of America’s Maxwell Medallion. Nine of her books have been Lambda Literary Award Finalists.

Ms. Newman wrote Heather Has Two Mommies, the first children’s book to portray lesbian families in a positive way, and has followed up this pioneering work with several more children’s books on lesbian and gay families: Felicia’s Favorite Story, Too Far Away to Touch, Saturday Is Pattyday, Mommy, Mama, and Me, and Daddy, Papa, and Me.

She is also the author of many books for adults that deal with lesbian identity, Jewish identity and the intersection and collision between the two. Other topics Ms. Newman explores include AIDS, eating disorders, butch/femme relationships, and sexual abuse. Her award-winning short story, A Letter To Harvey Milk, has been made into a film and adapted for the stage.

In addition to being an author, Ms. Newman is a popular guest lecturer, and has spoken on college campuses across the country including Harvard University, Yale University, the University of Oregon, Bryn Mawr College, Smith College and the University of Judaism. From 2005-2009, Lesléa was on the faculty of the Stonecoast MFA program at the University of Southern Maine. From 2008-2010, she served as the Poet Laureate of Northampton, MA. She has taught fiction writing at Clark University and currently she is a faculty mentor at Spalding University’s School of Creative and Professional Writing.